Why can chord shapes be moved on the guitar?

I recently received a comment on a YouTube video asking why chord shapes can be moved. I was only able to give a concise response on a video comment, but I felt it warranted a fuller explanation for anyone else who has the same question.

There’s a simple way to learn this, and a more in-depth theory understanding. In this article, I’ll cover both.

Let’s start with the simple way.

The simple reason guitar chords can be moved along the fretboard

The easiest answer is that if you play a chord without open strings (such as an E major, or a barre chord), you can move it along to any other fret using the same strings and it will be another valid chord. That’s because the relative position of each note remains the same i.e. the shape is the same.

For example, if you play the fretted strings of an A chord - fret 2 on strings DGB - you can move that shape along. Just don’t play the open A string at the same time.

If you moved along one fret, so you’re playing fret 3 on strings DGB, you’d be playing an A# chord. If you moved along another fret, you’d play B.

Remember, this is exactly how barre chords work. You take the E or A shape and move it along the neck - the “barre” aspect is simply to close the open strings from those chords, with your index finger essentially replacing the nut.

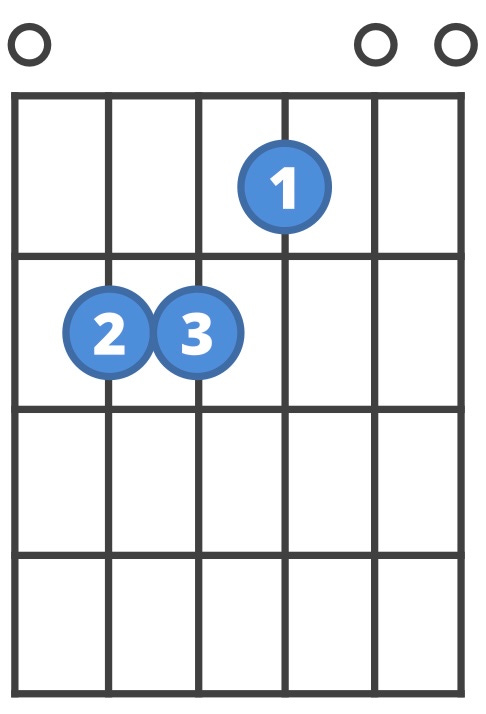

Here is an open E major chord (image from ChordBank):

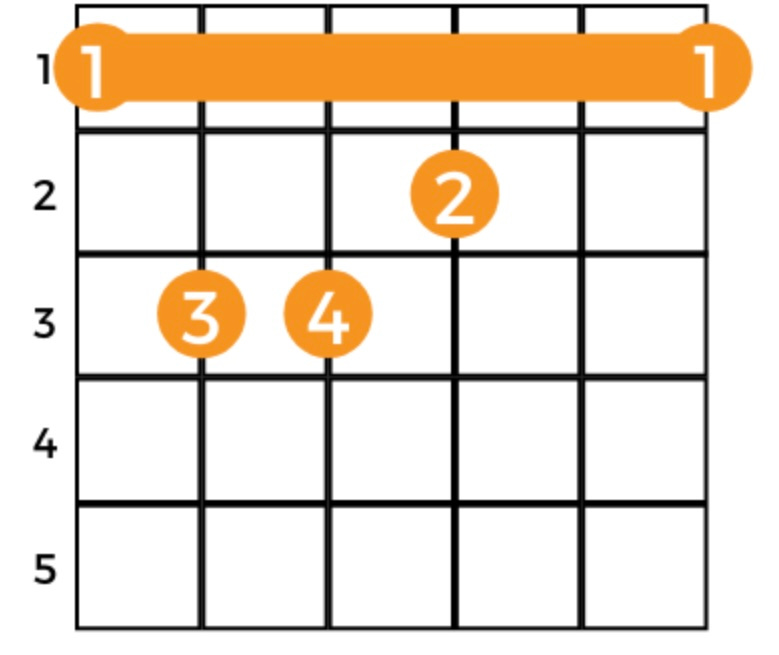

And here is a barre chord, using the E Major shape (from Music Grotto):

Notice that the two chords look identical, and the barre chord has your index finger covering the open strings.

The reason you don’t want to move chord shapes with open strings is simply because you’re then mixing notes that may not belong together.

So remember: a chord with closed strings can be moved up or down the fretboard and it will be a real chord, and you can use its open position name to know what it is. For example if you play D minor and slide it along three frets, it would be F minor. Two more from there, G minor.

The concept is the same as scales. You probably already know that if you play the minor pentatonic scale starting in fret 5, it’s A minor, but if you play it in fret 7 it’s B minor. And you probably also know that the reason it’s the same scale even when played in different places is because the same pattern of notes is being played. It’s the same with chords - same pattern of notes. The only exception is if you change strings (e.g. E major and A minor are the same shape, but one is minor and one is major), and if you incorporate open strings.

And this brings us nicely to the theory-based answer:

The theory way

Chords are named after the intervals inside them. To build a major chord, we take the intervals 1 3 5 from the major scale.

A minor chord also uses 1 3 5, but the 3 is flattened.

A seventh chord introduces the 7 interval.

There are other chords, but the principle is always the same: a chord must have specific intervals within it. You can’t have a major chord with a flattened 3, for example.

So the reason you can play a chord and move it is because the collection of intervals remains the same, but the note names change - so instead of playing a C chord with the notes C E G, you move up two frets and play a D chord with the notes D F# A. It’s the same intervals, just the names change.

See, a scale is simply a collection of specific intervals. An interval is just a fancy word that really means the distance from one note to another. The second note in the major scale is called the 2. The third note? The 3. Yeah, it’s that easy.

So the reason you can keep the same scale shape whether you’re playing in the fifth fret or the seventh, or eleventh, is because the scale is what it is because of intervals - and the placement of them in relation to each other always stays the same. If you’re playing a root note, you’ll always find a 2 just two frets along.

Here’s a quick video showing how to start finding intervals from your root note:

Like I said, it’s the same with chords as with scales. A chord uses particular intervals and their placement is always the same in relation to one another, so once you’ve made a shape you can just slide it up and down the neck.